“Easy chanting”? — You take one look at the lines below and you think, “Easy?” — no way.

But take a second look. All you have to know for reading this chant is up and down. You don’t have to know quarter-notes or full-notes or half-notes, or anything like that. The rhythm is your speech rhythm, whatever feels right to you. Up and down at your own speech rhythm.

The up and down is the one you’ve been hearing all your life. It’s the scale you learned in grade school — Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti, Do. And you start on a note of your own choosing, whatever feels right to you. You chant up and down from there.

That’s it. Plainsong is much easier to read than modern notation.

Furthermore, every setting on this site has an audio file at the beginning for you to play and thus get the chant pattern into your head. That, along with the plainsong score tells you what to sing.

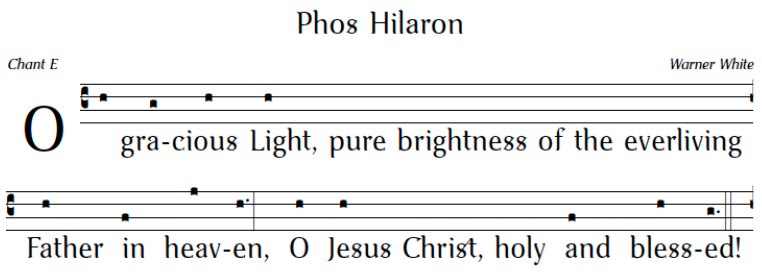

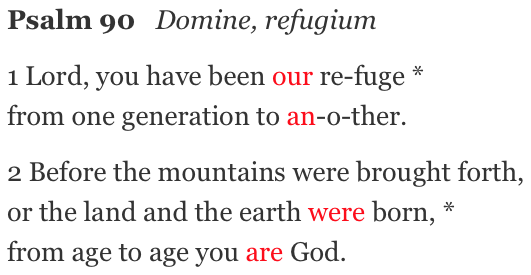

Let me give you an example. Here’s how you see the first two verses of Psalm 90.

You get the score, then the audio file (played by a bassoon), and then the psalm verses pointed. (I’ll explain the pointing in a moment.)

Here I am chanting it —

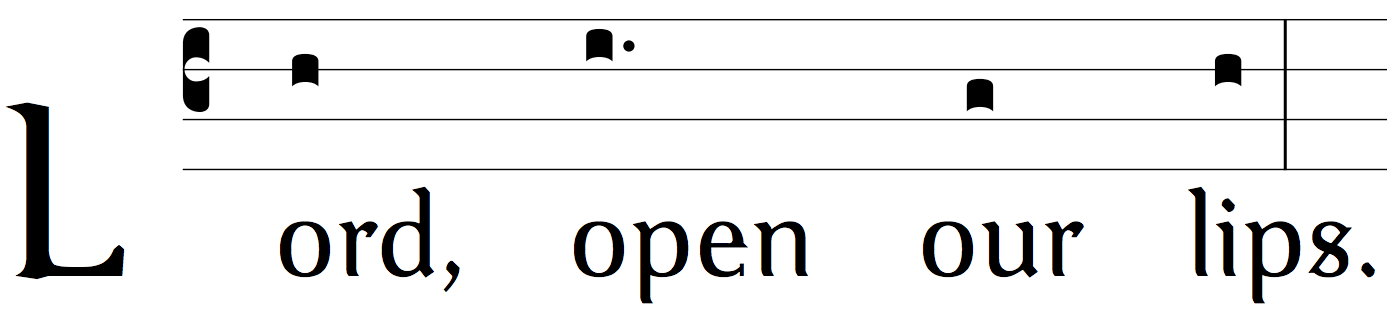

I start the first verse on a convenient note. It’s represented by the blank square. I chant on that note — it’s called the reciting note — until I come to a syllable in red. Then I go down two notes for the syllable our, then up four notes for the syllable re, and then down for the final syllables of the half-verse (in this case, just the one syllable fuge).

I begin the second half-verse on the reciting note and continue to the syllable in red, where I follow the same procedure as before, except with some difference in the intervals — down two for an, up four for o, then down one for the conclusion.

The second verse goes the same except that this time the half-verses end on accented rather than unaccented syllables.

There’s the flexibility. This why these chants are called flexible chants (F-chants). They provide for ending half-verses either on accented or unaccented syllables. (More about this shortly.)

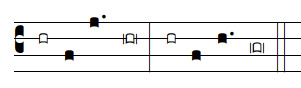

Notice also that it’s one note per syllable. Monkish plainsong is much more elaborate. They chant many times a day for a lifetime; so they get bored and want more variety. But we want to keep it simple. There are a couple of exceptions to the simplicity — the alleluia at the end of the invitatories and the ending notes of one or two of the canticles. But these variations are easy and intuitive. Here, for example, is the alleluia at the end of the invitatories —

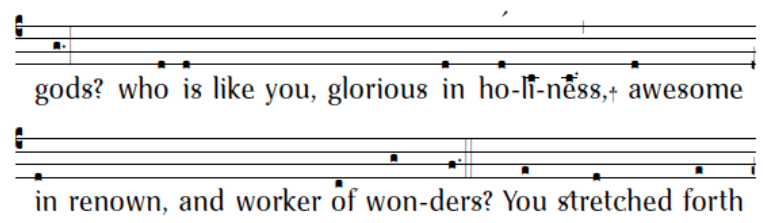

One other wrinkle occurs in the Song of Moses. There’s a very long half-verse. You can sing it on one note if you want, but for variety’s sake you can briefly drop down two notes and then come back up to the reciting note. Here it is —

You are reciting the long phrase,”who is like you, glorious in holiness, awesome in renown.” Above the syllable ho there’s an accent mark. It tells you that you can drop down on the next syllable for two syllables and then come back up. This is the only such reciting variation in these chants.

And that’s it! You now know all you need to know about using these chants. But if you want to know more, there’s a very good, simple introduction to plainsong at http://www.ccwatershed.org/Gregorian/.

Now what’s the scoop with F-chants?

When you listen to monks chanting the traditional plainsong settings you hear prayer. The words — even if you understand the Latin easily — have little significance. The chant is a means of meditation, for the monks as cantors, and for you as listener.

That can be done in English, but not so well. English moves from consonant to consonant and with a different accent pattern from Latin. In Latin the half-verses almost always end on an accented syllable. The chants have been developed accordingly. But in English the half-verses frequently end on a textually unaccented syllable. The consequence is a mismatch between tone and text.

Several attempts have been made over the years to alter the traditional tones in adjustment to this difference. They have involved adding a note or two, as needed, at the end of the first half-verse. By and large these attempts have succeeded — for the first halves of the verses. But the second halves have retained the problem.

I decided to alter the ending half-verses in the same way. At first I tried to take a traditional chant and alter it as little as possible, but succeeded with only one — traditional Tonus IId-2, which I turned into Chant A. All of the other chants are original.

So in these chants textual accent and musical accent match. The consequence is to bring out meaning. When your chant and your text go together in accent, meaning is emphasized. These chants thrust meaning upon you.

I do not claim that chanting with meaning is better than chanting in prayerful meditation. But there it is. We have the choice.